A brief history of American winemaking

Originally by Liz Thach for The Conversation

The American love affair with wine dates back to the earlier European settlers in the 16th century, when they began making wine with a native grape known as muscadine.

Today every state produces wine, though almost half of the more than 9,700 wineries are based in California.

While I don’t own a winery, I do tend to a small hobby vineyard and make my own garagiste wine. I also study the wine business. In honor of National Wine Day, here’s a primer on the history of the U.S. wine industry.

Settlers on the vine

When Spanish explorer Ponce de Leon arrived in what is now Florida in 1513, he was followed a half century later by Spanish and French Huguenot settlers, who began making muscadine wine.

Efforts to plant the great wines of Europe – known as Vitis vinifera or classic grapes – failed because their rootstock couldn’t withstand attacks from pests like phylloxera, which thrive in wet climates.

An interesting historical footnote is that Thomas Jefferson attempted to establish a winery and plant Vitis vinifera vineyards in Virginia in the late 1700s and early 1800s. He was, like the others, unsuccessful due to attacks of black rot and phylloxera.

But that didn’t stop wineries from popping up all over the East Coast and Midwest, including in Wisconsin, Ohio and New Jersey. Because of the threat of phylloxera, they used grapes that are native to the U.S. such as Concord and Niagara or hybrids like Catawba and Marechal Foch, as they still do today.

Brotherhood Winery in New York, for example, established in 1839 and the oldest continually operated winery in the U.S., continues to use some native American grapes as well as the classic Vitis vinfera, especially Riesling.

So it wasn’t until Spanish Missionaries discovered the dry climate of New Mexico in 1629 with its sandy soils that the first Vitis vinifera vineyards were planted in what is now the United States. They planted Mission grapes brought over from Spain.

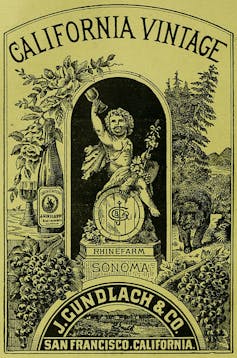

Wine comes to California

Wine didn’t come to California until 1769, when the Spanish started a mission in San Diego, with accompanying vineyards. As they settled further north, they established 20 more missions, concluding with one in Sonoma in 1823. Napa Valley began growing grapes in the 1830s.

Today, of course, due to its dry and sunny climate, which is perfect for grape growing, California produces more than 90 percent of U.S. wine.

In 2016, the U.S. produced 3 billion liters of wine, making it the fourth-largest in the world after Italy, France and Spain. At same time, Americans drink the most of any country – some 3.59 billion liters in 2016, or about 11.1 liters per person.

Jefferson, a passionate wine connoisseur, would be proud.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.